13

Oct

Exposition of Threads in a Speech

The public presentation of a speech (when unsupported by visual aids) is an interesting form of discourse because it contains little-to-no explicit structure. Typically, a speech is delivered (or read) with very few indications of structure presented to the listener (or reader). Because they are designed to be spoken aloud and heard, there are no chapter titles or section headings in the text. At best, the speaker may pause to indicate a change of topic, or reveal a bit of structure by saying “now I’m going to talk about,†or, “let me give you an example.â€

However, there is structure present in a speech. The speaker must present evidence or examples to support their goals, whether their goals are to persuade, inform, or entertain. They may also draw conclusions, ask relevant questions, or predict, all based on their evidence and conclusions. In order for the speech to be successful, the evidence, conclusions, and predictions must be logically tied together to build a coherent argument. In a well-crafted speech, the audience will have no trouble following the thread of the argument, despite the lack of explicit structure. However, if there is more than a small amount of content in the speech, the audience may not have the ability to rank the importance of various ideas, or even to identify the key concepts.

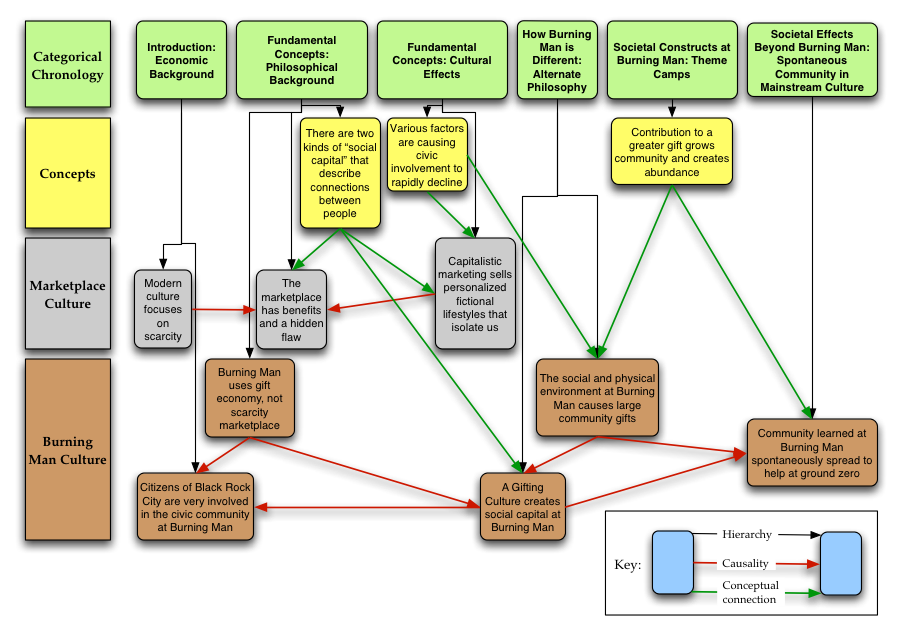

This is a diagram I created of the first half of the speech Viva Las Xmas [PDF, HTML] by Larry Harvey (2002), the founder of the Burning Man project. In the speech, he discusses some socioeconomic principles, and how they affect interactions between people in a marketplace economy, and also in the gift economy at Burning Man. The diagram uses placement, color, and links to show not only the chronology, hierarchical, and topical groupings of chunks of the speech, but also causality and conceptual connections among the chunks.

This has some significant consequences. Not only does the diagram immediately reveal the topical threads in the speech, it also makes the important concepts clear by virtue of their relatively high number of links to other portions of the speech. The connections, relationships, and implications that are implicit in the speech become explicit in the diagram, thereby conveying more complete knowledge to the reader, reducing the amount of raw information that they have to integrate, and making the actual message of the speech more accessible. This type of diagram could be constructed before the presentation of a speech, and then used to support the speech as it was being delivered. This would enable the speech author to emphasize the key points and make the speech easier to follow. This diagram reveals six dimensions of complexity.

- hierarchical membership, indicated by the horizontal position below the green boxes and redundantly encoded with the vertical black arrows

- topical grouping, indicated by the vertical position and redundantly encoded by color

- specific chunk, indicated by the text in each box

- chronological sequence, indicated by relative left to right position

- causality, indicated by red arrows

- conceptual connection, indicated by green arrows

I created this diagram in the fall of 2003. The diagram and the text of this post appear in my thesis.

Comments temporarily disabled due to spam.

12

Oct

Hierarchy of a Book

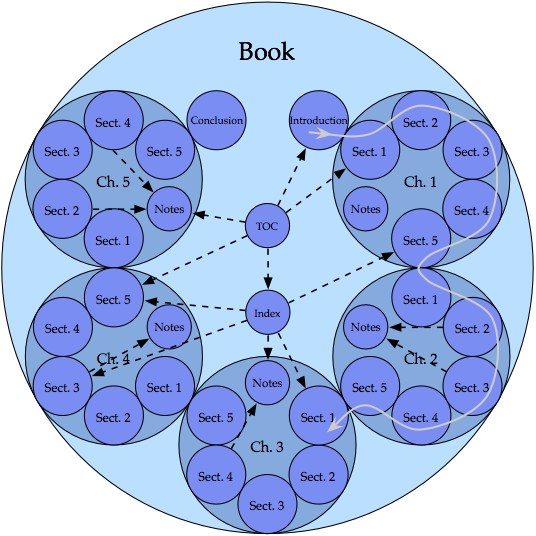

This diagram has been arranged to show not only the hierarchy, but also the intended use pattern of a typical, linear, non-fiction book.

- Continuity in the book is indicated by contact of the circles.

- The gray line, progressing in small and large clockwise arcs from section to section and chapter to chapter, demonstrates the linear progression of the content.

- The dashed black arrows show some possible non-linear paths that may be traveled by the reader to view content that is not part of the main linear flow of the book.

The goal of displaying the use of the book, and not merely the hierarchy, has led to an atypical diagram that conveys more knowledge than the typical counterpart.

I created this diagram in the fall of 2003. It appears in my thesis, and was selected to be supporting material for the book The Practical Guide to Information Design, by Ronnie Lipton.

12

Oct

Generation of Complex Diagrams: How to Make Lasagna Instead of Spaghetti

Update 2011: Many of the ideas in this thesis have evolved and been carried over into my book Designing Data Visualizations.

My master’s thesis is a system for creating good diagrams. It starts with the basics of perception and cognition, and walks the reader through the process of making appropriate choices for their particular design problem.

From the abstract:

This thesis presents a system for the generation of complex diagrams. “Complexity†is defined as a measure of distinct data types that are independently visually encoded. Diagrams representing four or more types of data are defined as complex, while diagrams representing three or fewer are simple. Successful generation of complex diagrams is dependent on appropriate design choices. Five fundamental principles are introduced to guide the choices made by the diagram designer. The two contextual fundamental principles are “different goals require different methods,†addressing the needs of the diagram designer, and “audience brings context with them,†addressing the needs and context of the diagram reader. The three perceptual fundamental principles are the “principle of information availability,†which guides the selection and density of the diagram elements, the “principle of semantic distance,†which guides the spatial placement and grouping of the diagram elements, and the “principle of informative changes,†which guides the visual encoding of the diagram elements. A review of the diagram design process, comprising selection, encoding, and placement of the diagram components, is given. For each phase of the design process the influence of the appropriate fundamental principles is discussed, and the fundamental principles are extended into applied guidelines and suggestions.